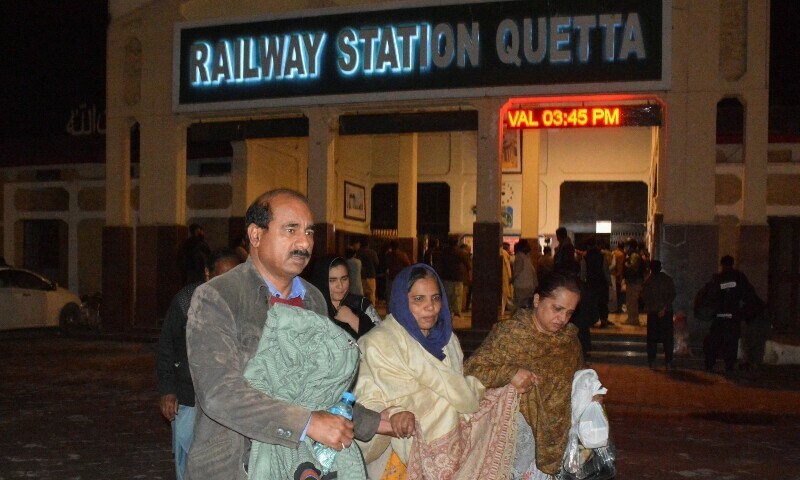

Bashir Ahmed lives in a two-room government quarter in Quetta. A father of five children who are currently on winter vacation, he is constantly being asked when they will travel to Peshawar.

Before annual examinations, the children were planning to spend their winter vacations with cousins in Peshawar. Ahmed has also been invited to the wedding of a close relative, scheduled in Peshawar for the first week of January.

In his words, his wife and children look at him expectantly every day when he returns from work, hoping that their tickets to Peshawar have been booked and the date for their journey has been fixed.

“I wanted to take my family to Peshawar on the Jaffar Express … It is the only train available for travel to Punjab and Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, as all others have been discontinued,” Ahmed tells Dawn.

But how can he think of putting his family aboard the train that comes under attack near the Bolan Pass on a weekly basis?

Rocket attacks, railway tracks and bridges being blown up, and attempted terrorist attacks on the train have become a commonplace occurrence now, with most people too scared to take the Jaffar Express.

This is not a new phenomenon: those old enough to remember would recall that attacks on railway tracks and gas pipelines have been a standard occurrence since the insurgency started in Balochistan in the year 2000.

However, passenger trains running between Quetta and the rest of the country have not faced such a volley of attacks since the 1970s, when the province experienced its first major insurgency, during the regime of then-prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

The trigger was the first, and deadliest, attack of the year — the hijacking of the Peshawar-bound passenger train by Baloch separatist terrorists on March 11. At the time, the train was carrying around 500 passengers, including women, children and security personnel.

It was stopped and held hostage — along with its passengers — between the Hirk and Mushkaf areas, close to a tunnel. The hostage situation lasted for two days, resulting in several casualties among passengers and security personnel.

However, a subsequent operation by security forces prevented any further loss of life, with the train and the remaining passengers being successfully rescued.

“The hijacking of the Jaffar Express was the biggest and worst terrorist incident to have taken place in Balochistan during 2025,” a senior security official tells Dawn, adding that since then, the Jaffar Express had become a primary target for the separatist elements.

Deadly alternative

One might think that if the train is no longer a safe bet, one can always travel by road.

But there is a catch: passenger coaches that run between Quetta and every major city of Pakistan have also been in terrorists’ crosshairs, with several tragic incidents occurring over the past 18 months in which armed men allegedly intercepted coaches and, after checking identity papers, dragged out passengers who did not belong to Balochistan and executed them.

The situation worsened when bomb and suicide attacks and firing incidents started taking place on the national highways that link Balochistan with other provinces.

The takeover of highways by armed groups further created fear among the people, prompting the Balochistan government to impose a ban on night travel by coaches, buses and other forms of transport.

‘Business as usual’

But railway authorities have a different perspective on travel via the Jaffar Express. While acknowledging the frequent attacks on railway tracks and bridges, they insist that passenger numbers on the train are still quite encouraging.

“We have bookings for the Jaffar Express up to Jan 10,” Muhammad Kashif, the railway chief controller in Quetta, tells Dawn.

While that may be true, it is also a fact that during the past year, the line used by the Jaffar Express witnessed at least 10 incidents of track blasting, which sometimes led to the suspension of train services.

Similarly, at least one railway bridge was blown up, while four derailment incidents also took place at different areas along the route this year.

The train also faced sabotage twice, in the Shikarpur and Jacobabad areas of Sindh, while in a separate incident, five bogies were derailed and some passengers were injured in Jacobabad.

When asked why militants were only targeting the Jaffar Express, Quetta Divisional Superintendent (DS) Imran Hayat said that while its final destination was Peshawar, the train travels through Punjab.

“This is not something new; such attacks have been taking place here since 1877,” he says, referring to the time when the British Raj first built a railway through the Bolan Pass, connecting Sibi and Quetta.

At the time, the tribes living in the area considered it an occupation of their lands and resisted the only way they knew how — by attacking the train, which was the main physical manifestation of the colonisers that passed through their territory.

In view of such attacks, the colonial rulers established a levies force, recruiting people from local tribes to protect the railway lines and tunnels built through the Bolan Pass.

According to Hayat, this route was actually built by the British Empire for strategic, rather than commercial, purposes.

The line passes through difficult mountainous terrain, but with towering mountains on both sides of the track, it is tough going. Security forces are positioned in Aab-i-Gum, Mach and Kolpur, from where they monitor the line and provide security.

The March 11 hijacking occurred in just such an area, near a tunnel surrounded by mountains and difficult terrain. Officials Dawn spoke to attributed the casualties incurred in the incident to the remote location of the terrorist attack, which was eventually put down by SSG commandos.

According to Hayat, there has been no major attack on the Jaffar Express since the hijacking attempt in March. However, track blasting, damage to railway bridges and other disruptions have occurred, but these, he claims, were not fatal.

The only exception was a derailment following a blast on the railway track in Dasht area of Mastung district, in which eight passengers were slightly injured.

“Many other attacks were staged on the track and train in Nasirabad, Jaffarabad and Kachhi districts, but no significant losses took place. Sometimes, the train service between Quetta and the rest of the country had to be suspended as a result of the track being blown up,” a railway official says.

Presently, three trains run from Quetta: the Jaffar Express to Peshawar, the Bolan Mail to Karachi and the Chaman Passenger to the border with Afghanistan.

All other trains, including the Akbar Bugti, Chiltan Express, Awami Express, Sindh Express, Quetta Passenger and Harnai Passenger, were cancelled by Pakistan Railways over the past five years or so.

‘Symbolic, strategic importance’

Security experts believe that the Jaffar Express is targeted due to its strategic role: security personnel, including army troops, use it to travel to Punjab and KP. People living in Balochistan also use the Jaffar Express for travel.

Muhammad Amir Rana, a security analyst and director of the Pakistan Institute for Peace Studies (PIPS) in Islamabad, is of the opinion that the train passes through a critical railway route, which connects Balochistan with the rest of the country.

It is widely used by Baloch students studying in Punjab, Punjab-based families and lower-ranking public sector employees, including personnel from various security services. This civilian-heavy passenger profile gives the route both symbolic and strategic importance, making it a prime target for insurgent groups.

“An attack on the Jaffar Express carries repercussions far beyond Balochistan. Its impact is felt strongly in Punjab, which is precisely what insurgents seek: to widen the psychological and political footprint of violence and draw national attention,” Rana said, explaining why the train remains a preferred target for miscreants.

The most dangerous stretch of the route passes through areas where multiple insurgent groups, including the proscribed Baloch Liberation Army (BLA), Baloch Republican Army (BRA) and their allied factions, have a significant presence.

Securing this corridor is particularly challenging due to the rugged terrain, limited access points and the vast expanse of difficult geography.

But, he says, “despite these risks, the state cannot afford to suspend or abandon the service. Doing so would amount to conceding space and narrative to the insurgents, granting them a symbolic victory and reinforcing their ability to disrupt vital civilian connectivity.”

Best-laid plans

For Bashir Ahmed — the father of five — all of these are risks he can’t afford.

“I cannot take the risk of travelling with my family on the Jaffar Express or by coach, nor can I afford to travel by air, as all airlines, even PIA, have increased the prices of air tickets,” he said.

Even ministers and MPAs have taken this issue to the assembly, saying they cannot purchase such exorbitantly priced air tickets.

“How can a government employee travel with his family by air?” Ahmed asks, before revealing that he has cancelled his plans to visit Peshawar and will spend the winter vacations in Quetta instead.

Dawn – Homenone@none.com (Saleem Shahid)Read More