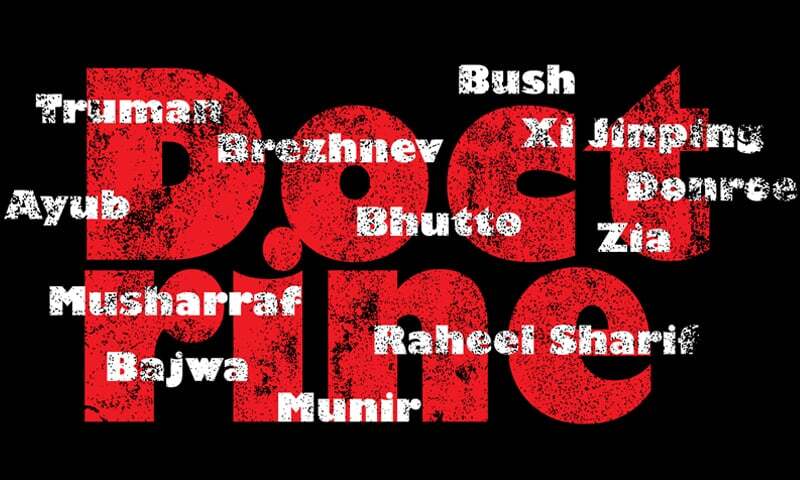

In the theatre of global politics, a ‘doctrine’ is more than just a policy paper. It is a nation’s strategic DNA. From the 1823 Monroe Doctrine, which fenced off the western hemisphere from European monarchs, to the 1947 Truman Doctrine that looked to aggressively ‘contain’ Soviet communism, these blueprints signal a country’s core values, and the consequences for those who cross them.

In 1968, the Soviet Union introduced the Brezhnev Doctrine, asserting Moscow’s right to militarily intervene in socialist countries being threatened by capitalist/pro-US forces. Fast forward to the 21st century, and the blueprints have become increasingly aggressive.

We’ve seen the Bush Doctrine’s ‘strike first, ask questions later’ approach (‘preemptive strikes’), and Russia’s Gerasimov Doctrine, which treats disinformation and cyberattacks as the new artillery. We see the Xi Jinping Doctrine seeking to enhance China’s glory through the sprawling veins of the Belt and Road Initiative, while Donald Trump’s recent ‘Donroe’ Doctrine is an obsession with border walls, drug cartels and keeping Chinese influence out of ‘America’s backyard.’

But doctrines are not static. They mutate. They adapt to the scent of power and economic reality. This is apparent in Pakistan as well. Pakistan began with its founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah’s high-minded idealism, but was quickly forced into a security-first straitjacket by the shadow of a much larger India.

Pakistan’s national ‘doctrine’ has continued to mutate according to the whims of those in power, thus resulting in an often erratic and haphazard approach to strategy-building

By 1958, the harsh realities of the Cold War had taken hold. Upon seizing power, Gen Ayub Khan established a doctrine that firmly anchored Pakistan within Western alliances. This manoeuvre was shaped to leverage US military and economic assistance to balance the scales with India, while simultaneously energising an ambitious industrialisation and modernisation programme at home.

The Ayub regime fell in 1969. Under another dictator, Gen Yahya Khan, the country’s eastern wing broke away in 1971 to become Bangladesh. Rising to power in the wake of the 1971 crisis, Zulfikar Ali Bhutto, whose party had secured a majority in the country’s western wing during the 1970 elections, began to forge a new national path.

Bhutto’s doctrine was designed to reinvent Pakistan’s identity and champion a strategy that moved away from heavy Western dependency in favour of stronger ties with oil-rich Arab states, the ‘Islamic Bloc’, and the burgeoning ‘Third World’ movement. Most significantly, the doctrine established the groundwork for Pakistan’s nuclear programme, which Bhutto envisioned as the essential equaliser to offset India’s military strength.

Bhutto’s regime fell in a military coup in 1977. The coup-maker, Gen Ziaul Haq decided to stay on. A Zia Doctrine emerged. It prioritised a policy of domestic ‘Islamisation’, while positioning Pakistan as a frontline state in a US-backed anti-Soviet ‘Afghan jihad.’ Consequently, the Zia dictatorship secured extensive American support, which Zia used as a cover to accelerate the country’s nuclear programme under a cloak of plausible deniability.

During this era, the concept of ‘strategic depth’ also took root. This strategy sought to establish a pro-Pakistan government in Afghanistan, to ensure a secure territory where Pakistani armed forces could regroup in the event of conflict with India. Following Zia’s death in a 1988 plane crash, the Zia Doctrine remained a powerful influence over Pakistan’s foreign and domestic policies throughout the turbulent ‘decade of democracy’ that followed.

In 1999, the political landscape shifted again when Gen Pervez Musharraf seized power in a coup. Now there was a Musharraf Doctrine. It was fundamentally defined by the global upheaval of the 9/11 attacks. Adopting a ‘Pakistan first’ mantra, Musharraf attempted to balance a high-stakes role as a key US ally in the ‘War on Terror’ with a domestic social vision known as ‘enlightened moderation.’

However, the doctrine ultimately collapsed as the country faced the dual pressures of surging Islamist militancy and widespread internal unrest. From 2008 onward, a ‘hybrid system’ began to take shape, creating a political mechanism through which civilian governments were elected to office but remained tethered to strategic doctrines drafted by the military leadership.

A landmark shift occurred in 2013, with the emergence of the Raheel Sharif Doctrine, authored by the-then army chief. This doctrine represented a fundamental departure from traditional thinking by officially acknowledging that internal militancy posed a far greater existential threat to Pakistan than its historical rivalry with India.

This shift was swiftly operationalised through a massive military offensive launched to dismantle Islamist sanctuaries and neutralise militant networks. Then, a Bajwa Doctrine surfaced during the tenure of Imran Khan, marking an attempt by former army chief Gen Qamar Javed Bajwa to once again alter Pakistan’s national security focus. The core of this doctrine was a shift toward geo-economics, prioritising regional trade, transit and the infrastructure connectivity promised by the China-Pakistan Economic Corridor (CPEC).

However, this vision ultimately fractured under the weight of mounting civil-military discord. While the military leadership sought regional stability to facilitate economic growth, the Khan administration remained preoccupied with an aggressive campaign against political rivals and a polarising effort to ‘rehabilitate’ Islamist militants.

This divergence in priorities, exacerbated by the stagnation of key CPEC projects, strained the working relationship between Khan and Bajwa. The resulting deadlock concluded in 2022, with Khan’s removal from office through a parliamentary vote of no-confidence.

Appointed as Bajwa’s successor by a Pakistan Muslim League-Nawaz (PML-N)-led coalition, Gen Asim Munir oversaw the emergence of what is often referred to as the ‘Munir Model.’ Its outcome is perhaps the most rooted institutionalisation of military authority in Pakistan’s history.

At its heart lies the concept of economic sovereignty, a framework where the military has moved to take a more active role in steering the nation’s economics. Strategically, the model is defined by a ‘zero-tolerance’ posture, as it maintains a relentless, uncompromising stance against Islamist militants and Baloch separatists.

The model views internal security and economic stability as two sides of the same coin. By fusing state survival with economic growth and military muscle, the doctrine aims to project Pakistan as an assertive regional power. Geopolitically, the Munir Model is characterised by an intense anti-India tilt. It is deeply pro-China, and closely aligned with Saudi Arabia, while maintaining a pragmatic engagement with the US.

Domestically, the model identifies political populism as an existential threat to the state’s functional integrity. Notably, the doctrine seeks to trim the Islamist dimension from Pakistani nationalism that was added by the Zia Doctrine.

While Munir’s doctrine remains rooted in Pakistani nationalism, it replaces Islamist fervour with a brand of ‘rational Islam’ and hard-nosed pragmatism. The model has been a success on many fronts, but it will continue to be tested in an increasingly turbulent and mutating geopolitical landscape.

Published in Dawn, EOS, January 18th, 2026

Dawn – Homenone@none.com (Nadeem F. Paracha)Read More