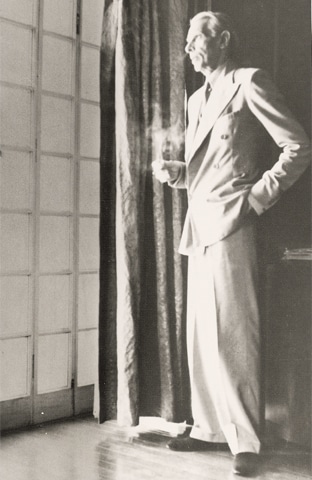

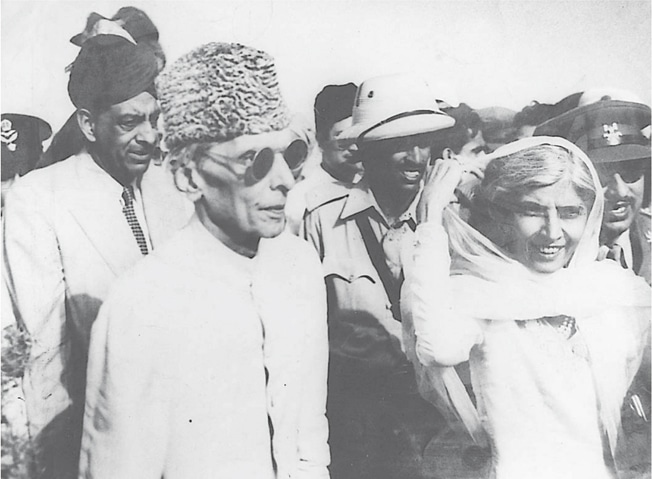

IN the current phase of our beautiful, beleaguered country’s history, institutional deviation and constitutional deformities have reached abysmal lows. This special report is being published on the birthday of an individual who had unshakable respect for institutional integrity and individual accountability in life, not immunity for life. The invitation to write encouraged one to consider anecdotal aspects to portray the Quaid’s life from inception to conclusion through fleeting glimpses, snatches of scenes, bits and pieces, which juxtaposed together, evoke his unlikely beginnings, unique persona, values and respect for institutions.

So much is already widely known about the pivotal role of M.A. Jinnah, especially between 1935 and 1948. One therefore decided to select relatively less known aspects. Herein are segments from the Quaid’s early years and then, with a deliberate leap over the next 40 years or so, random clips from the last 13 months.

A disconcerting birth

For data about his arrival on earth, and early years, one relied on the account recorded by his sister Fatima Jinnah.

She spent the most time with him. In addition to being one of his six siblings, she also spent a total of 28 years with him as his sole housekeeping custodian and sister, in two phases. Initially from about 1910 to 1918. Then, following Ruttie Jinnah’s death in February, 1929 (after about 10 years of a tumultuous marriage from 1919 to 1929), for a total of 26 years, living in close proximity, and frequent interaction. Her book My Brother presumed to have been written about 15 years after his demise during 1963-64, was published in 1967. Though the late eminent scholar Sharif ul Mujahid states in his preface that “… an extremely controversial passage…” had to be excluded, the published version comprises only three chapters which “…truthfully reproduce…” the contents of the original manuscript, now stored in the National Archives, Islamabad.

With the most reputed midwife of Karachi attending to a home-based delivery in 1876 by mother Mithibai, Fatima Jinnah writes; “… the baby boy was weak and tiny, having slim, long hands, and a long, elongated head. The parents were seriously worried about his health, this little baby that was underweight by quite a few pounds…” Despite the doctor’s assurance that the low weight factor should not cause worry, Mithibai insisted that her spouse Jinnah Poonja, herself and the baby travel soonest to Ganod in the small princely state of Gondal, Kathiawar where the venerated holy man Hasan Pir was buried, to seek his blessings for her frail first-born.

Braving a storm en route by sailing boat through the Arabian Sea, to the port of Verawal, thence by bullock cart through village Paneli to the destination of the great Sufi’s tomb, Mithibai and Jinnah Poonja fondly saw the tiny tot’s head shaved for the aqeeqa. With silent, saintly blessings absorbed, the return to Karachi commenced with a rich feast in Paneli where all villagers joined to celebrate the birth of the boy named Mohammad Ali.

There was a poignant contrast in the last stretch. Just as Pakistan’s genesis moved towards the triumph of reality, the great leader’s already frail body was being eroded from within. His fragility became increasingly apparent around, and onwards of 1940.

An unstudious boy

Yet even though he was already the apple – and the orange – of his mother’s eye, his early childhood years worried his father. The boy was far more interested in “…abandoning books for marbles, tops, gilli danda and cricket…”.

He had already joined, and soon left, a primary school close to his home in Kharadar because he spurned studies and classrooms. Prematurely, to please his father, he insisted on attending to office work. But soon, his virtual illiteracy prevented participation in conduct of transactions and business. In just two months, the light dawned.

He told his father: “… I would like to go back to school”. He then “…wanted to make up for lost time, as boys of his age and even younger than him had gone ahead of him. He took to his lessons with a vengeance, studying into the late hours of the night at home, determined to forge ahead….” But another disappointment came up. The teacher told his father that “…the boy is horrible in arithmetic….” was ominous news for a businessman who wanted his son to secure future financial bonanzas. He decided to take the boy to a school a long mile away from home, far enough from distracting local friends.

And so the ten-year-old gained admission in 1886 to the fourth standard Gujarati in the well-reputed Sind Madrassah. But, it soon seemed the boy was incorrigible. He “…continued to woo success and victory on the playfield, rather than at school….”

When the boy’s aunt, Manbai Poofivisited Karachi from her Bombay home to spend a few days with her brother Jinnah Poonja and his family, it was agreed that the unstudious boy would proceed with her to Bombay to be admitted to the Anjuman-i-Islam School where, fortuitously, he passed the fourth standard exam, “…enabling him to be admitted in first standard English….” Despite this success, a mother’s love prevailed over a father’s ambitions. The boy soon returned to Karachi, to be readmitted to Sind Madrassah on December 23, 1887. Some unease abided, to resurface four years later. For, on his son’s insistence, his father moved him out of the prestigious school on January 5, 1891 to be admitted to the Catholic Missionary High School on Lawrence Road where the boy became restless yet again. Just a month later, he was returned to Sind Madrassah on February 9, 1891 in fourth standard English.

Equestrian adventures

Meanwhile, back at the Kharadar ranch, the boy who would not settle into school found stallions far more exciting. Using his father’s fine stable of horses, accompanied by a friend named Karim Kassim, the two would make the other two whose reins they held, trot and gallop for long hours every day. Moving swiftly between horse-carriages on the streets of Karachi, the most visible means of transport for the well-off, or ‘aristocratic’ families, the errant son continued to cause concern to his doting parents. Mithibai would steadfastly declare that her Mohammad Ali would one day become a great man.

England beckons

As General Manager of Graham Trading and Shipping Company — an enterprise in close commercial contact with Jinnah Poonja’s firm – Frederick Croft should be credited for initiating a transformative phase in the life of a restless 16-year-old teenager. He suggested that the boy be sent to London to work at the head office of Croft’s firm for about three years where, among other skills, he could also gain high proficiency in English while learning to adjust to new challenges. Intense debate ensued between the parents. Mithibai most reluctantly agreed to allow her beloved firstborn to leave – provided he was first wed to prevent him from being entrapped by an English woman. The search led to 15-year-old Emibai in distant Paneli village, Kathiawar.

The family then proceeded again by boat from Karachi to Verawal, then by bullock cart to the bride’s home. After lavish festivities, the new couple returned to Karachi. Soon thereafter, with his mother’s tears and prayers blending for a heart-wrenching farewell, the son began the three-week journey to what became a four-year life-changing experience. The father had already remitted a large sum to London to pay for his expenses.

Sent to learn commerce, the youth soon learnt much more elsewhere. Mohammad Ali listened to debates in the House of Commons, to rhetoric at Hyde Park Speakers’ Corner, viewed Shakespeare’s plays, noted the names of Prophet Muhammad (peace be upon him) inscribed in Lincoln’s Inn as one of the world’s greatest law-givers, canvassed votes for Bombay Zoroastrian, and earlier, one of the four founders of the Congress Party, Dadabhai Naoroji’s narrow victory as the first non-Englishman elected from a London constituency to parliament.

In short, Jinnah rejected the very reason for being sent to England by his father. Instead, as recounted by him about half a century later in 1946 to Nasim Ahmed, Dawn’s correspondent in London, he even considered a career on the stage. His appetite for acting … possibly as Romeo … was whetted by brief experience with a touring company. Until his shocked father, who belatedly learnt of new plans, instantly and categorically ruled that out.

All the while, he preserved chastity.

When his Russell Street landlady’s pretty daughter reminded him that they happened to be “standing together chatting under a mistletoe on Christmas Eve and that custom required the man to kiss the woman”, Jinnah politely declined to do so because, as he told her, his faith and culture did not permit such indulgence. did fall head over heels in love with reading, and voraciously so.

From newspapers to law books to poetry to plays by Shakespeare. From the extreme of abandoning books in childhood to cherishing their infinite value as he grew into adulthood.

He was also recovering from the news of dual tragedies at home. First his childbride Emibai’s death who he barely knew, followed by the profound loss of one he knew from his very first breath, his adoring mother Mithibai who passed away giving birth to her seventh child.

Perhaps these two traumas instilled a new resolve — to fulfill his mother’s dreams and be the youngest ever law student to become a barrister from Lincoln’s Inn. Then return to Karachi, and Bombay, to help his father recover from the huge losses suffered in business.

From trials to new heights

Preferring law practice in larger Bombay to small-town Karachi from 1897 to about 1900 was like an anti-climax to the hopes nurtured by success in the London exams. His secretary in later years, M.H. Saiyid in his book Mohammad Ali Jinnah (A Political Study), in 1945 wrote: “The first three years were of great hardship and although he attended his office regularly every day, he wandered without a single brief. The long and crowded footpaths of Bombay may, if they could only speak, bear testimony to a young pedestrian pacing them every morning from his new abode in a humble locality in the city, to his office in the Fort, and every evening back again to his apartments after a weary, toilsome day spent in anxious expectation.”

Ironically, momentous change yet again began through the intervention of an Englishman, John Macpherson, the acting advocate-general of Bombay. Jinnah became the first-ever local practitioner to be invited to work in the advocate general’s chamber. Obviously, some hint of the intelligence and potential possessed by the young barrister must have come through to the senior luminary who was later knighted. Hearing about a vacancy for a temporary presidency magistrate, the freshly-recruited lawyer boldly initiated contact with his employer ‘s support, and Sir Charles Olivant, member in-charge of the judicial department, who then became the third Englishman to play a catalytic role in opening dramatic new vistas for Jinnah’s ascent to outstanding professional success.

Forty years later

Many articles by other writers published in Dawn have already done justice to crucial phases of the founder’s life between 1900 and 1940. In this rumination, while even excluding glimpses of his singular love for Ruttie Jinnah, arbitrary focus is on random segments between 1940 and 1948.

Age, frailty and fanaticism

Except for Mahatma Gandhi, born in 1869, who was seven years older than Jinnah, the Muslim League’s leader was the oldest among the three most important political figures who played decisive roles in the creation of Pakistan and India. Gandhi had an overarching influence but did not wield the operational Congress policy direction that Nehru did. The latter was born in 1889. He was thirteen years younger and was 58 years old at Independence while Mountbatten was 24 years younger and was only 47 years of age in 1947.

Jinnah, at 71, was the oldest of the three protagonists. But was also the one most notably becoming physically vulnerable to ill-health.

In 1953, A.R. Casey, the governor of Bengal in 1946, noted that “I have looked up my personal diary, and I find that I emphasised, in several references, the fact that he (M.A. Jinnah) looked very frail.” However, he could sustain long periods of active discussion without any sign of tiring …a couple of hours at a time…. My wife and I dined with him and his sister at Government House in Karachi … in March 1948. At this same dinner my wife made some comment about someone or other being “a fanatic.” Jinnah said, “Don’t decry fanatics. If I hadn’t been a fanatic, there would never have been Pakistan.”

August 7, 1947

As the Dakota aircraft afforded an aerial overview of New Delhi soon after taking off with the Quaid, Fatima Jinnah and his small staff on its way to Karachi, the first ADC to the founder, Mian Ata Rabbani was seated immediately behind his leader. He noticed how the Quaid looked intently down at the city and softly said to himself: “That is the end of it”.

Yet, in two respects at least, it was not the end of his ties with India. He did not change his will whereby Aligarh Muslim University remained one of the principal beneficiaries. Nor did he sell his favourite residence on Mount Pleasant Road in Bombay.

Later, the same day, after the boisterous welcome in Karachi, as the Quaid ascended the steps of the Governor-General’s House, he said to his military adviser and ADC Lt. S.M Ahsan: “Do you know, I never expected to see Pakistan in my lifetime. We have to be very grateful to God for what we have achieved. “ Later still, during the orientation walk through the premises of his new residence, and a meticulous inspection of the inventory, he noted that the library shelves were empty.

He was informed that the previous occupant, the Governor of Sind, had taken all the books with him. Visibly upset, Jinnah said to his military secretary, “Nonsense. The books belong here. Go and get them back”. Similarly, when he was shown game items, he was told that a croquet set had been taken away by Sir Francis Mudie, Governor of Punjab. On his visit to Lahore after some time, he had the set retrieved and returned to where it belonged as state property.

August 9, 1947

At a dinner hosted by Sir Ghulam Hussain Hidayatullah in Jinnah’s honour, Mrs Hidayatullah tied an imaam zaamin on the founder’s arm. Surprisingly, he did not know the meaning of the ritual. When told that it would protect him against evil, he turned to Altaf Hussain, the editor of Dawn, and said, “Now I can face you”, to loud laughter.

‘Unforgetting’ & unforgiving?

In his book I was ADC to the Quaid, which was written after his retirement, Group Captain Ata Rabbani recalls an unusual revelation of Jinnah’s traits.

He records that, while proceeding to the Sind Assembly on August 11, 1947 to deliver the address that became a historic landmark of secular vision, the Quaid-i-Azam deliberately ignored the presence of A.K.M Fazlul Haque, the East Bengal leader who had the honour of moving the Lahore Resolution on March 23, 1940 at the Muslim League meeting. Well in advance of coming abreast of the Quaid walking in his direction, Fazlul Haque greeted him several times and also bowed respectfully. Jinnah neither looked at him nor responded to the salutation.

Rabbani wrote: “…The only reason that comes to mind is that (Fazlul Haque, otherwise known for his integrity) had repeatedly acted against the categorical instructions of the League’s high command, at times even at the peril of causing damage to the overall Muslim cause. Disloyalty to the cause was one thing that the Quaid-iAzam would not forgive.”

The final stretch

There was a poignant contrast in the last stretch. Just as Pakistan’s genesis moved towards the triumph of reality, the leader’s already frail body was being eroded from within.

His fragility became increasingly apparent around, and onwards of 1940.

Now in Pakistan, the news poured in every day of ghastly massacres as refugees crossed new state frontiers in Punjab, of anti-Muslim slaughters in New Delhi and Bihar, Indian occupation of Srinagar on a forged Instrument of Accession, severe shortage of funds and resources to cope with enormous new numbers and pressures — all compounded the depressive impact on both mind and physique.

Yet he insisted on reviewing piles of files in detail, made notes, frequently met the prime minister and other senior individuals. And also travelled to Peshawar, Risalpur, Lahore.

Then, defying all advice, he flew from Quetta to Karachi to inaugurate the State Bank on July 1, 1948, his last public appearance.

Both Fatima Jinnah in her slim book and Lt. Colonel Dr Ilahi Bakhsh, who wrote With the Quaid-i-Azam during his last days as he attended to him in the last weeks, narrate moving accounts of how this giant of a man, despite valiant efforts, quickly weakened each day in August and early September 1948. Yet his sense of values survived. When a nurse repeatedly declined to tell him his temperature unless the doctor permitted her, and then left the room, he told his sister: “I like people like that… people who can be firm, who refuse to be cowed down….”

Towards the end of August, Fatima Jinnah recalled him saying: “I am no more interested in living…the sooner I go the better.” When she reassured him that the doctors were hopeful, he said, “No… I don ‘ t want to live.”

The bizarre episode of the ambulance breakdown on September 11, 1948 between Mauripur airfield and the Governor-General’s House is well known.

Frail at birth and in death

Weight count came a full circle.

From cradle to grave. Infected lungs and sheer fatigue had reduced him to only 70 pounds. Yet, when it mattered most, Jinnah punched way above his physical weight.

In every sense, the Quaid-i-Azam remained the unbeaten heavy-weight champion of history. He defeated three adversaries virtually single-handedly — the British, the Congress Party and allies, plus at least four Muslim entities that opposed the creation of Pakistan.

Though well-known, Stanley Wolpert’s distinctive tribute in his book, Jinnah of Pakistan bears repetition: “Few individuals significantly alter the course of history. Fewer still modify the map of the world. Hardly anyone can be credited with creating a nation-state.

Mohammad Ali Jinnah did all three.”

The writer is an author, a former senator and federal minister.

email: javedjabbar.2@gmail.com

Dawn – Homenone@none.com (Javed Jabbar)Read More